Nicholas Anthony

The Biden administration has not let up in its “war on junk fees,” or perhaps more accurately, its war on prices. The latest round of attacks came from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) announcing a proposal to further restrict overdraft fees.

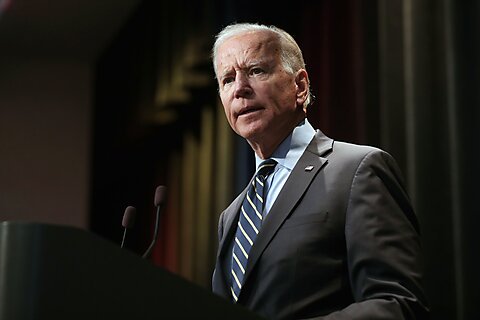

The idea of bringing down prices when inflation is still on everyone’s mind is likely to play well in headlines for President Biden’s re‐election campaign. However, this initiative will do nothing to help consumers if these services are regulated out of existence. And if the administration refuses to let the market decide which fees are too high for overdraft services, that’s exactly what could happen.

Principles Matter

The history of price controls is mainly a history of government‐created shortages. Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee were quick to correct promotional materials from the Biden administration to explain the reality of the situation. The problem is something that any student of Econ101 should recognize. Establishing a price control below the market price will result in demand exceeding supply—in other words, price controls create shortages. What comes next is where it can get complicated.

As Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee noted, these restrictions can result in a service being shut down completely. Although some banks have been able to afford to drop or reduce fees, others may not have the luxury. In practice, that means people will lose access to the service entirely once it becomes too costly to offer.

Yet that’s not the only consequence. The price controls could also result in banks increasing fees for other services in an attempt to recoup losses. So, options like free or low‐cost checking accounts, travel rewards, and the like could become a thing of the past.

Although President Biden has been quick to label overdraft services as “exploitation” in a bid to rally support, policymakers should not lose sight of the extended consequences of these restrictions.

Rather, officials eager to enact change should take another path. My colleague, Norbert Michel, said it best last year when he explained that if politicians truly believe services are priced too high, then they should get into the business and undercut the competition. Doing so would avoid the mess of establishing industry‐wide rules, create what is purportedly missing from the market, and mark the leading official as a pioneer in the industry—a win for everyone.

To be clear, there should be consequences if banks create fraudulent transactions to then initiate an overdraft fee that wouldn’t have otherwise occurred or if banks permit overdrafts after a person opts out of the service. However, so long as fraud is not occurring and people can freely opt into this service, the government should stay out of the equation.

Fees in Context

Aside from these principles, now is a particularly strange time to be going after overdraft fee revenue given that it has been steadily dropping for years. For example, researchers at Curinos found that overdraft fees fell by 68 percent between 2008 and 2023 (Figure 1). Likewise, researchers at Bankrate found that overdraft fees fell by 11 percent between 2022 and 2023. Even the CFPB has recognized this trend. In a May 2023 report, the CFPB found that revenue from overdraft and insufficient fund fees “for the fourth quarter of 2022 alone was approximately $1.5 billion lower than in the fourth quarter of 2019.”

What’s most interesting is that, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Competition—from other banks and nonbank providers such as fintech firms—arguably has affected overdraft practices more than anything else.” For example, researchers at Curinos also found that although consumers often knowingly use overdraft services and appreciate the option, new competitors (e.g., new banks and fintechs) that have improved overdraft services experienced higher customer acquisition than banks that failed to innovate.

In other words, competition has already been leading to more affordable services. In fact, many incumbent banks have changed their overdraft practices and even eliminated overdraft fees (Table 1).

Finally, to the extent that someone experiences problems with overdraft fees but does not wish to switch banks, there are many ways to avoid running into trouble. As noted above, people must opt‐in and agree to use overdraft services, but it’s not a lifetime commitment. People can also later call their bank to opt out of the service.

Likewise, setting up automatic transfers from a savings account can help create an additional buffer. Finally, whether it is through automated alerts or routine accounting, monitoring one’s transactions can help ensure neither a declined transaction nor an overdraft fee comes as a surprise.

Conclusion

It’s a free and open marketplace that makes products and services more affordable, not ever‐tightening restrictions. As the Consumer Bankers for America President and CEO Lindsey Johnson explained, “[The CFPB’s] proposal on overdraft price setting is just the latest in a myriad of unnecessary and costly regulations by this Administration that seems guided by political polling, rather than by sound policy created by what should be independent agencies.”

Whether it’s restricting overdraft fees or credit card late fees, the CFPB’s price controls are likely to succeed in only one thing: limiting the supply of financial services. If the proposal is enacted, the sudden price change may score political points in the short term, but consumers will suffer from the absence of services in the long term.